Terrible Things - Story Notes

|

Terrible Things

There was a psychology professor at my college who was infamous for experimenting on his own children. He was interested in the use of isolation techniques as punishment, and would lock his children in some kind of dark box and then make us listen to hour-long recordings of them screaming to be let out. How could he do that, I wondered. The answer, I believe, was that he simply didn’t think that what he was doing was wrong. That, to me, is all the horror any story needs. Years later, I saw a documentary in which an evolutionary anthropologist explained that Neanderthals threw their young out to fend for themselves at a younger age, while another branch of early humans (Cro-Magnon, I believe) kept and nurtured their young much longer, causing their brains to become more developed and superior. Which led me to wonder––what if someone tried to put that theory to the test in the modern world? I sent this story to Michael Kelly at Shadows & Tall Trees who liked it but said that the end wasn’t quite right, and provided a few brilliant suggestions that I gladly took. Terrible Things wouldn’t have turned out as well as it did without his intelligence and generosity. |

Intruders

In November of 2017 I was invited by David Longhorn to submit a story for a special edition of Supernatural Tales. David published my first strange story back in 2011, and Supernatural Tales has always been one of my favorite places to find outstanding dark fiction, so I wanted to do something worthy.

It had been a while since I’d written a ghost story, and I knew that I wanted to write one. I began, as I often do, with a question––what is a ghost? Does it always have to be the spirit of a dead person, a manifestation from the past? Or can a ghost come from the future, a manifestation or vision of who and what a person will become?

Every teacher knows the experience of encountering their former students, now grown older. It can be a moving and gratifying experience, but it can also be unexpectedly disorienting. As a teaching artist, I’ve had the pleasure of returning to the same New York City school every year to work with 6th and 7th graders. The 8th grade students, who are now “too old” for me to teach, pass me in the hallway, looking strangely older and somehow more unhappy. When our eyes meet, it feels uncomfortable, like we’re now in two different worlds, and the sensation is like having just seen a ghost—I wondered if it felt the same way to them. That feeling of mutual ghostliness found its way into this story.

In spite of what others may think or say, 'Intruders' is not a story about school shootings––I would never attempt to write such a story. I have, in fact, participated in active shooter drills in public schools and have seen their traumatic effect on children and teachers. Still, I didn’t write this story to address any of those social or political issues. For me, this is a story about one man’s confusion about where the emotional boundaries lie between himself and the children he’s dedicated his life to helping, and the tricky role of truth-telling in those relationships.

Writings Found In a Red Notebook.

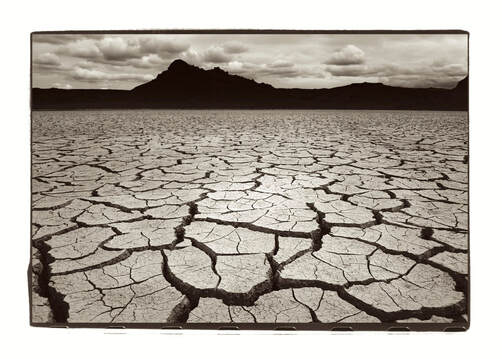

The genesis of this story was a road trip I once took with my first wife and her mother across the Nebraska Badlands. As we drove further and further west, the earth beneath us became cracked and barren, and the horizon became more and more flat and featureless, until at one point, I looked around us and saw a vast emptiness that looked nothing like the planet I was raised on. We did in fact get lost there, although only temporarily. The scene about being pursued across a desert road by a truck at night is absolutely true (including the ancient, corpse-like cowboy at the wheel). The unearthly moonscape where the unlucky couple ends up is based on a real place, Toadstool National Park, whose Google pics do not effectively communicate its profound and disturbing unearthliness. I remember staring up at those lunar outcroppings, then all around at that vacant horizon, when my mother-in-law said cheerily, “Let’s camp here tonight.” No, I said. Absolutely not. We moved on. But I always wondered––what might have happened if we’d stayed?

The genesis of this story was a road trip I once took with my first wife and her mother across the Nebraska Badlands. As we drove further and further west, the earth beneath us became cracked and barren, and the horizon became more and more flat and featureless, until at one point, I looked around us and saw a vast emptiness that looked nothing like the planet I was raised on. We did in fact get lost there, although only temporarily. The scene about being pursued across a desert road by a truck at night is absolutely true (including the ancient, corpse-like cowboy at the wheel). The unearthly moonscape where the unlucky couple ends up is based on a real place, Toadstool National Park, whose Google pics do not effectively communicate its profound and disturbing unearthliness. I remember staring up at those lunar outcroppings, then all around at that vacant horizon, when my mother-in-law said cheerily, “Let’s camp here tonight.” No, I said. Absolutely not. We moved on. But I always wondered––what might have happened if we’d stayed?

Faces of the Missing

After years of writing stories set in the American South while living in NYC, ‘Faces of the Missing’ was my first New York story. One of the many ways in which stories are like dreams is that to dream or write about a place effectively, you need to have memories that are distant enough to be transformed by your imagination. This story draws on my early memories of haunting the Lower East Side when things were edgier, and the distance between the art scene and a crime scene was very short indeed.

New York City has a way of devouring the weak, and people can find themselves disappearing both psychologically and physically, like our unlucky narrator. I was also interested in how some people are drawn to stronger, dominant people like Carter and end up sort of disappearing into them. I’ve almost disappeared like that more than once myself, so I wrote this story as a sort of cautionary tale.

After years of writing stories set in the American South while living in NYC, ‘Faces of the Missing’ was my first New York story. One of the many ways in which stories are like dreams is that to dream or write about a place effectively, you need to have memories that are distant enough to be transformed by your imagination. This story draws on my early memories of haunting the Lower East Side when things were edgier, and the distance between the art scene and a crime scene was very short indeed.

New York City has a way of devouring the weak, and people can find themselves disappearing both psychologically and physically, like our unlucky narrator. I was also interested in how some people are drawn to stronger, dominant people like Carter and end up sort of disappearing into them. I’ve almost disappeared like that more than once myself, so I wrote this story as a sort of cautionary tale.

Something You Leave Behind

This story started out as a relatively realistic piece, just a troubled couple having a conversation in a diner in a strange town. Later, I went back to it and let the ‘weird’ come out.

It’s based on a real place that my first wife and I stumbled across years ago; the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in Weston, Virginia. Like the couple in the story, we were exhausted and starving, and pulled off the road to find a place to eat. When the asylum rose up in front of us, we had no idea what it was, until we saw the sign. (Since then, I’ve learned that it’s the largest hand-cut sandstone building in the world, other than the Kremlin.) The conversation with the waitress was 100% real. Her suggestion that we should move to this dark little town made us laugh, but it also got under my skin and made me start to question, why not? The more I thought about it, the more making important life choices––making any choice at all––suddenly felt terrifyingly random. That feeling started to overwhelm me––until the coffee and fried chicken finally arrived. Those wild thoughts were fueled by exhaustion and hunger; thankfully, it’s hard to spiral downward into an existential black hole when there’s coffee and fried chicken right in front of you.

I’ve worked closely with mental patients for many years, so when I wrote this story, I knew I didn’t want to write a typical abandoned-asylum-horror story––IOW, I didn’t want to make the mental patients (or their disembodied spirits, etc.) be the source of the threat or an object of revulsion. Like Mr. Poe tried to show us, the most frightening madness is always our own. If I succeeded at all in doing that, I’m glad.

Many years later, I returned to this place, curious to see if it was as creepy as I remembered. Some local entrepreneur had bought the asylum, fixed it up, and started giving tours. Julia and I were walking up to the front door when we looked inside and caught a glimpse of a tour guide dressed in an old-fashioned white nurse’s uniform––that felt like too much, so we turned around and left.

This story started out as a relatively realistic piece, just a troubled couple having a conversation in a diner in a strange town. Later, I went back to it and let the ‘weird’ come out.

It’s based on a real place that my first wife and I stumbled across years ago; the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in Weston, Virginia. Like the couple in the story, we were exhausted and starving, and pulled off the road to find a place to eat. When the asylum rose up in front of us, we had no idea what it was, until we saw the sign. (Since then, I’ve learned that it’s the largest hand-cut sandstone building in the world, other than the Kremlin.) The conversation with the waitress was 100% real. Her suggestion that we should move to this dark little town made us laugh, but it also got under my skin and made me start to question, why not? The more I thought about it, the more making important life choices––making any choice at all––suddenly felt terrifyingly random. That feeling started to overwhelm me––until the coffee and fried chicken finally arrived. Those wild thoughts were fueled by exhaustion and hunger; thankfully, it’s hard to spiral downward into an existential black hole when there’s coffee and fried chicken right in front of you.

I’ve worked closely with mental patients for many years, so when I wrote this story, I knew I didn’t want to write a typical abandoned-asylum-horror story––IOW, I didn’t want to make the mental patients (or their disembodied spirits, etc.) be the source of the threat or an object of revulsion. Like Mr. Poe tried to show us, the most frightening madness is always our own. If I succeeded at all in doing that, I’m glad.

Many years later, I returned to this place, curious to see if it was as creepy as I remembered. Some local entrepreneur had bought the asylum, fixed it up, and started giving tours. Julia and I were walking up to the front door when we looked inside and caught a glimpse of a tour guide dressed in an old-fashioned white nurse’s uniform––that felt like too much, so we turned around and left.

The Truth About What Happens After Death, A Short Film In One Reel

When I was in college, I used to work in the Audiovisual Library. In those days, that meant loading heavy 16 millimeter projectors on carts into the back of a van and rolling them into different classrooms where we showed flickering celluloid educational films. (The one mentioned in the story, ‘Emergency Childbirth’, was real––and yes, students did faint.)

Part of the job was to repair broken films, so I spent many hours splicing them together with a razor blade and glue. One day, I thought it might be fun to take all the little scraps of broken film that were bound for the trash can and splice them into a crazy, surrealistic work of art. I remember threading that patchwork film into the viewer and pressing Play, then the explosion of garbled noise and insane images that came rushing out. It was genuinely frightening, and I had to turn it off. It almost felt like I hadn’t made it, that it had somehow made itself. The memory of that sensation and the barrage of surreal images was probably behind the visions that the main character experiences in the final passage.

I’ve heard at least one reader confess that they’re not exactly sure what this story is about, which frankly surprises me, because it’s right there in the title (the first half of it, anyway).

The Gospel singer whose face had burned off in a plane wreck was also real. I saw him late one night on the PTL club, which I used to watch in order to get angry and yell at the TV, which I somehow believed was a good use of my time. The televangelist’s comments were also real. I didn’t throw a beer bottle through the picture tube like the character in my story does, but I do remember throwing my shoe. (I think I missed.)

When I was in college, I used to work in the Audiovisual Library. In those days, that meant loading heavy 16 millimeter projectors on carts into the back of a van and rolling them into different classrooms where we showed flickering celluloid educational films. (The one mentioned in the story, ‘Emergency Childbirth’, was real––and yes, students did faint.)

Part of the job was to repair broken films, so I spent many hours splicing them together with a razor blade and glue. One day, I thought it might be fun to take all the little scraps of broken film that were bound for the trash can and splice them into a crazy, surrealistic work of art. I remember threading that patchwork film into the viewer and pressing Play, then the explosion of garbled noise and insane images that came rushing out. It was genuinely frightening, and I had to turn it off. It almost felt like I hadn’t made it, that it had somehow made itself. The memory of that sensation and the barrage of surreal images was probably behind the visions that the main character experiences in the final passage.

I’ve heard at least one reader confess that they’re not exactly sure what this story is about, which frankly surprises me, because it’s right there in the title (the first half of it, anyway).

The Gospel singer whose face had burned off in a plane wreck was also real. I saw him late one night on the PTL club, which I used to watch in order to get angry and yell at the TV, which I somehow believed was a good use of my time. The televangelist’s comments were also real. I didn’t throw a beer bottle through the picture tube like the character in my story does, but I do remember throwing my shoe. (I think I missed.)

The Sea In Darkness Calls

This story was written for a themed anthology from Dark Minds Press, Darkest Minds, edited by Ross Warren and Anthony Watson, in which the theme was “crossing borders.”

The strange green-lit window in the story is something that I actually saw when I was walking through a neighborhood at dusk, although I can’t remember where. (Washington DC? Rockport, Massachusetts?) It was nighttime where I was standing, but on the other side of that window, it was brightest daylight––or so it seemed. It was one of those indelible moments when time seems to stop, and you just stand there trying to make sense of what you’re seeing. Even now, I’m still not sure. Out of moments of confusion like that come stories like this.

Another experience that found its way into this story happened when I took my young daughter and her friend to Coney Island for a day at the beach. There had been a drowning there the day before due to dangerous rip-tides, and an NYPD boat was just offshore, dragging the water for the child’s body. A television news crew was grabbing people and interviewing them, asking whether or not they were scared to go in the water––or, in my case, let my kid go in the water. I wouldn’t let my daughter swim––I’d seen that police boat––so we were wading, about knee-high in the freezing dark waves, when I felt something that felt like long hair wrap itself around my leg. I don’t think I screamed, but I probably came as close to it as I ever have in my adult life. It was seaweed, of course, and I tore it off and threw it as far as I could, which was not far enough for me. That moment, and the strange bright window, and how easy it was for me at the time to imagine a man who feels himself losing everything, all came together in this story.

Usually, whenever I write a story for a themed anthology, it gets turned down, and I end up placing it elsewhere. (It’s a kind of game I play with the universe, and vice versa.) But this time, the editors took it, so I must have been doing something right.

This story was written for a themed anthology from Dark Minds Press, Darkest Minds, edited by Ross Warren and Anthony Watson, in which the theme was “crossing borders.”

The strange green-lit window in the story is something that I actually saw when I was walking through a neighborhood at dusk, although I can’t remember where. (Washington DC? Rockport, Massachusetts?) It was nighttime where I was standing, but on the other side of that window, it was brightest daylight––or so it seemed. It was one of those indelible moments when time seems to stop, and you just stand there trying to make sense of what you’re seeing. Even now, I’m still not sure. Out of moments of confusion like that come stories like this.

Another experience that found its way into this story happened when I took my young daughter and her friend to Coney Island for a day at the beach. There had been a drowning there the day before due to dangerous rip-tides, and an NYPD boat was just offshore, dragging the water for the child’s body. A television news crew was grabbing people and interviewing them, asking whether or not they were scared to go in the water––or, in my case, let my kid go in the water. I wouldn’t let my daughter swim––I’d seen that police boat––so we were wading, about knee-high in the freezing dark waves, when I felt something that felt like long hair wrap itself around my leg. I don’t think I screamed, but I probably came as close to it as I ever have in my adult life. It was seaweed, of course, and I tore it off and threw it as far as I could, which was not far enough for me. That moment, and the strange bright window, and how easy it was for me at the time to imagine a man who feels himself losing everything, all came together in this story.

Usually, whenever I write a story for a themed anthology, it gets turned down, and I end up placing it elsewhere. (It’s a kind of game I play with the universe, and vice versa.) But this time, the editors took it, so I must have been doing something right.

The Last Testament of Jacob Tyler

I wrote 'The Last Testament of Jacob Tyler' in a rented room in Brooklyn, sleeping on a leaky air mattress while suffering from a severe case of pertussis that I’d contracted from one of my daughter’s school friends, whose parents were anti-vaxers. I’d write a few paragraphs between wracking coughing fits; when I couldn’t breathe at all and started to choke, I’d grab the inhaler and take a hit, wait for my esophagus to relax and open, then start writing again. The anger and violence in Jacob Tyler’s voice probably came from that. It was also probably why one of the characters is dying from TB, so there may have been some kind of sympathetic magic at work––when I told that to a friend, he said, “Good thing you weren’t writing about the bubonic plague.”

This story is based on the Anti-Rent Wars in Delaware County, New York––in particular, the “Calico Indians’, masked vigilantes who terrorized local land owners and tax collectors in the early 1840s. I spent several summers in the little upstate towns where it all took place. To this day, if you go to the Post Office in Delhi, you can see a mural on the wall depicting the rebels doing battle in their hooded masks and antlers. (The masked “Indians” in my story may be a bit more terrifying than the real thing, but apparently the real thing was terrifying enough.)

While I suppose that most of my stories fall under the label of “quiet horror” (or at least semi-quiet), every once in a while, I find that I need to write––in Lynda Rucker’s excellent words––“a rollicking tall tale from hell in folk horror meets Old Testament-like mayhem and morality.”

I loved writing Jacob Tyler, but once I’d written it, I couldn’t imagine who would possibly want to publish it. It seemed too gleefully bloody and violent, too explicitly monstrous. Definitely not “quiet horror”. Then I read a post from the late great Charlie Black, inviting writers to submit stories for The Tenth Black Book of Horror. He made no bones about the old-school horror esthetic of the Black Books series: “I know this isn’t quite everyone’s cup of tea,” he wrote. I had a look and decided to take a shot. Charlie accepted Jacob Tyler. Since then, it’s gone on to have a life of its own, and recently received a truly excellent podcast treatment on Horror Tales, which you can listen to here (although you probably shouldn’t listen to it in the dark, no matter what the producers suggest): http://horrortalespodcast.com/episodes

I thought twice before including Jacob Tyler in the collection. I knew it was very different from the other twelve stories––was it too different?

A friend of mine who’d just been to see ‘The Blair Witch Project’ said to me, “You know, I’m all for the power of suggestion and everything…but when I pay money for a movie like that, I want to see something.” I think I wrote this story with him in mind. Because sometimes you need to see the monsters. Or, as Jacob Tyler himself says in the story’s last line, “If there is something coming for me, as it surely must, I want to see it when it comes.”

I wrote 'The Last Testament of Jacob Tyler' in a rented room in Brooklyn, sleeping on a leaky air mattress while suffering from a severe case of pertussis that I’d contracted from one of my daughter’s school friends, whose parents were anti-vaxers. I’d write a few paragraphs between wracking coughing fits; when I couldn’t breathe at all and started to choke, I’d grab the inhaler and take a hit, wait for my esophagus to relax and open, then start writing again. The anger and violence in Jacob Tyler’s voice probably came from that. It was also probably why one of the characters is dying from TB, so there may have been some kind of sympathetic magic at work––when I told that to a friend, he said, “Good thing you weren’t writing about the bubonic plague.”

This story is based on the Anti-Rent Wars in Delaware County, New York––in particular, the “Calico Indians’, masked vigilantes who terrorized local land owners and tax collectors in the early 1840s. I spent several summers in the little upstate towns where it all took place. To this day, if you go to the Post Office in Delhi, you can see a mural on the wall depicting the rebels doing battle in their hooded masks and antlers. (The masked “Indians” in my story may be a bit more terrifying than the real thing, but apparently the real thing was terrifying enough.)

While I suppose that most of my stories fall under the label of “quiet horror” (or at least semi-quiet), every once in a while, I find that I need to write––in Lynda Rucker’s excellent words––“a rollicking tall tale from hell in folk horror meets Old Testament-like mayhem and morality.”

I loved writing Jacob Tyler, but once I’d written it, I couldn’t imagine who would possibly want to publish it. It seemed too gleefully bloody and violent, too explicitly monstrous. Definitely not “quiet horror”. Then I read a post from the late great Charlie Black, inviting writers to submit stories for The Tenth Black Book of Horror. He made no bones about the old-school horror esthetic of the Black Books series: “I know this isn’t quite everyone’s cup of tea,” he wrote. I had a look and decided to take a shot. Charlie accepted Jacob Tyler. Since then, it’s gone on to have a life of its own, and recently received a truly excellent podcast treatment on Horror Tales, which you can listen to here (although you probably shouldn’t listen to it in the dark, no matter what the producers suggest): http://horrortalespodcast.com/episodes

I thought twice before including Jacob Tyler in the collection. I knew it was very different from the other twelve stories––was it too different?

A friend of mine who’d just been to see ‘The Blair Witch Project’ said to me, “You know, I’m all for the power of suggestion and everything…but when I pay money for a movie like that, I want to see something.” I think I wrote this story with him in mind. Because sometimes you need to see the monsters. Or, as Jacob Tyler himself says in the story’s last line, “If there is something coming for me, as it surely must, I want to see it when it comes.”

The Professor of History

The Professor’s house in this story was modeled after one that I saw every day when I was growing up. Known as “the Murder Mansion” or “the Martin Farmhouse”, it sat in a grove of old oak trees right at the end of my street. It had in fact been the site of a grisly multiple murder like the one briefly described in the story, and was said to be haunted. Like the house in the story, it was at least a hundred years old, and wholly unlike all the suburban homes that had sprung up all around it. The new owners were a truly lovely couple, both elderly academics from the local university, who did indeed keep their house overflowing with books in every available space (yes, even on the staircase, which impressed me mightily––obviously). They also took great pleasure in telling people (especially young people, on Halloween and at other times) the story of the murders, and would lead us to the front hallway at the foot of the stairs to show us the famous bloodstain on the floor. I tried, but could never really see it.

I wanted to write a Halloween story. I wanted to immortalize the house and my Halloween memories of it, but there was so much nostalgia built up around it in my mind, that the first draft was basically an affectionate memoir piece. Then I decided––don’t try to cut out the affection; let it have its place and run its course––then introduce a counter-narrative (the boy, his father, and missing mother) that’s as cold and cruel as the original memory was warm and lovely.

The elderly couple died some years ago. A new and more wealthy couple bought the house and built a large swimming pool behind it, which somehow feels wrong. Still, whenever I go back to the street where I grew up, and I see those high windows lit up at night through the old oak trees with their branches in “tangled arterial shapes”, the years fall away, and I feel an odd kind of happiness that while this old house has been the inspiration for many stories, mine is one of them.

The Professor’s house in this story was modeled after one that I saw every day when I was growing up. Known as “the Murder Mansion” or “the Martin Farmhouse”, it sat in a grove of old oak trees right at the end of my street. It had in fact been the site of a grisly multiple murder like the one briefly described in the story, and was said to be haunted. Like the house in the story, it was at least a hundred years old, and wholly unlike all the suburban homes that had sprung up all around it. The new owners were a truly lovely couple, both elderly academics from the local university, who did indeed keep their house overflowing with books in every available space (yes, even on the staircase, which impressed me mightily––obviously). They also took great pleasure in telling people (especially young people, on Halloween and at other times) the story of the murders, and would lead us to the front hallway at the foot of the stairs to show us the famous bloodstain on the floor. I tried, but could never really see it.

I wanted to write a Halloween story. I wanted to immortalize the house and my Halloween memories of it, but there was so much nostalgia built up around it in my mind, that the first draft was basically an affectionate memoir piece. Then I decided––don’t try to cut out the affection; let it have its place and run its course––then introduce a counter-narrative (the boy, his father, and missing mother) that’s as cold and cruel as the original memory was warm and lovely.

The elderly couple died some years ago. A new and more wealthy couple bought the house and built a large swimming pool behind it, which somehow feels wrong. Still, whenever I go back to the street where I grew up, and I see those high windows lit up at night through the old oak trees with their branches in “tangled arterial shapes”, the years fall away, and I feel an odd kind of happiness that while this old house has been the inspiration for many stories, mine is one of them.

The Smell of Red Clay

‘The Smell of Red Clay’ was the first story I wrote back when I was trying to learn how to write my own kind of ghost story. Sexual jealousy, at its worst, is a special kind of hell, so I let the main character start with both feet planted firmly in that fire. Throw in a little revisionist urban legend, a little blind-date-from-hell, and this story came to life. David Longhorn, the wise and wonderful editor of Supernatural Tales where this story first appeared, called it “an almost ghost story.” Some might say the ghost never shows up––I’d say it does.

‘The Smell of Red Clay’ was the first story I wrote back when I was trying to learn how to write my own kind of ghost story. Sexual jealousy, at its worst, is a special kind of hell, so I let the main character start with both feet planted firmly in that fire. Throw in a little revisionist urban legend, a little blind-date-from-hell, and this story came to life. David Longhorn, the wise and wonderful editor of Supernatural Tales where this story first appeared, called it “an almost ghost story.” Some might say the ghost never shows up––I’d say it does.

A Face In the Trees

I have no idea what prompted me to start writing this long story about a woman whose life changes when she goes to Sri Lanka. Usually, I can remember deciding to write a story, picking a topic or a memory to start building upon. This story just seemed to happen on its own. I think it had something to do with the main character, Alma. She became alive and real for me very quickly. I was concerned about her, and wanted to know what was going to happen to her. I knew that she was going to go through hell, but I found myself wanting her to come out on the other side. In a story with so much destruction, I didn’t want her to be destroyed. And (characteristically) she obliged.

The image of the saris fluttering in the treetops came from an interview I conducted years before with Joan Hogetsu Hoeberichts, a Zen Buddhist priest and social worker who went to Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the tsunami to conduct group therapy sessions with survivors. She told me that this was the one image that haunted her the most. That image haunted me as well, and found its way into this story.

Although I was writing a story partially set in a culture that is not mine, I took some confidence in the fact that my main character was also not of that culture, and was, in many ways, as clueless as I was. Still, I wanted to get things right, and to not misrepresent anything or anyone. As a practicing Buddhist, I was especially wary about misrepresenting the pirith ceremony for pacifying the spirits of the dead. So I reached out to Dr. Nalika Gajaweera, at the University of Southern California Center for Religion and Civic Culture, to make sure I had it right. Many thanks to her for her kind and thorough answers to my many questions.

I started writing this story not long after my wife and I moved into a huge brick apartment building in Irvington. Many bits and pieces of our life there found their way into the second half of this story. “Vanderberg Manor”, the historic mansion and grounds where Alma retreats after leaving Sri Lanka, is based on Lyndhurst, the property of 19th century robber baron Jay Gould, where Julia and I went walking almost every day at sunset. The staff of Lyndhurst do in fact decorate for Halloween––ghosts hang and flutter from the treetops, and scarecrow armies line the roads. The unearthly cries that Alma hears in the trees were inspired by the loud raccoon battles that woke my stepdaughter Katy every night. I never heard them myself, but her description alone was terrifying.

‘A Face In the Trees’ was the first of several stories I wrote that topped 10,000 words––a length that (as other writers know) is almost impossible to place anywhere. I also knew it didn’t fit easily into most editor’s definition of “horror”, “weird”, or other labels. After I’d run through the only two or three markets available for stories of that length, I knew this story would have to wait for the day when I had a collection published––so many thanks to Steve Shaw for helping this long and unclassifiable story finally see the light of day.

I have no idea what prompted me to start writing this long story about a woman whose life changes when she goes to Sri Lanka. Usually, I can remember deciding to write a story, picking a topic or a memory to start building upon. This story just seemed to happen on its own. I think it had something to do with the main character, Alma. She became alive and real for me very quickly. I was concerned about her, and wanted to know what was going to happen to her. I knew that she was going to go through hell, but I found myself wanting her to come out on the other side. In a story with so much destruction, I didn’t want her to be destroyed. And (characteristically) she obliged.

The image of the saris fluttering in the treetops came from an interview I conducted years before with Joan Hogetsu Hoeberichts, a Zen Buddhist priest and social worker who went to Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the tsunami to conduct group therapy sessions with survivors. She told me that this was the one image that haunted her the most. That image haunted me as well, and found its way into this story.

Although I was writing a story partially set in a culture that is not mine, I took some confidence in the fact that my main character was also not of that culture, and was, in many ways, as clueless as I was. Still, I wanted to get things right, and to not misrepresent anything or anyone. As a practicing Buddhist, I was especially wary about misrepresenting the pirith ceremony for pacifying the spirits of the dead. So I reached out to Dr. Nalika Gajaweera, at the University of Southern California Center for Religion and Civic Culture, to make sure I had it right. Many thanks to her for her kind and thorough answers to my many questions.

I started writing this story not long after my wife and I moved into a huge brick apartment building in Irvington. Many bits and pieces of our life there found their way into the second half of this story. “Vanderberg Manor”, the historic mansion and grounds where Alma retreats after leaving Sri Lanka, is based on Lyndhurst, the property of 19th century robber baron Jay Gould, where Julia and I went walking almost every day at sunset. The staff of Lyndhurst do in fact decorate for Halloween––ghosts hang and flutter from the treetops, and scarecrow armies line the roads. The unearthly cries that Alma hears in the trees were inspired by the loud raccoon battles that woke my stepdaughter Katy every night. I never heard them myself, but her description alone was terrifying.

‘A Face In the Trees’ was the first of several stories I wrote that topped 10,000 words––a length that (as other writers know) is almost impossible to place anywhere. I also knew it didn’t fit easily into most editor’s definition of “horror”, “weird”, or other labels. After I’d run through the only two or three markets available for stories of that length, I knew this story would have to wait for the day when I had a collection published––so many thanks to Steve Shaw for helping this long and unclassifiable story finally see the light of day.

The Sound That the World Makes

This story had its start, as many do, in a story that someone else told me. Three college friends of mine decided to visit a nearby monastery to see the monks perform their Christmas Eve rite. I’m fairly certain that the monastery was Gethsemane, made famous by Thomas Merton. My friends had a lovely time, apparently––unlike the unfortunate visitors in my story.

There’s a concept in Kadampa Buddhist mind training called inappropriate attention. It basically refers to the mind’s compulsive tendency to return again and again to a negative thought or memory until there’s no room in the mind for anything else. I know of people who’ve seen their loved ones die painfully, and for them, that single event erases every good memory of that person and renders all the positivity and happiness in that life and relationship null and void. We create our world with our minds, for better and for worse–– this story is about the “worse” part.

‘The Sound That the World Makes’ is, admittedly, one of the more unashamedly “scary” stories in the book. As M.P. Johnson said of this story in his Amazon review, “It will make you think twice about visiting a strange church for Christmas.” It was also the first story of mine that CM Muller took for his wonderful journal, Nightscript. It was and still is a thrill to appear in the pages of that beautifully made book.

Very little-known fact––'The Sound That the World Makes' was going to be the title for my first collection––that is, until Michael Kelly of Undertow Press convinced me to change the title to Terrible Things. Good call, sir.

This story had its start, as many do, in a story that someone else told me. Three college friends of mine decided to visit a nearby monastery to see the monks perform their Christmas Eve rite. I’m fairly certain that the monastery was Gethsemane, made famous by Thomas Merton. My friends had a lovely time, apparently––unlike the unfortunate visitors in my story.

There’s a concept in Kadampa Buddhist mind training called inappropriate attention. It basically refers to the mind’s compulsive tendency to return again and again to a negative thought or memory until there’s no room in the mind for anything else. I know of people who’ve seen their loved ones die painfully, and for them, that single event erases every good memory of that person and renders all the positivity and happiness in that life and relationship null and void. We create our world with our minds, for better and for worse–– this story is about the “worse” part.

‘The Sound That the World Makes’ is, admittedly, one of the more unashamedly “scary” stories in the book. As M.P. Johnson said of this story in his Amazon review, “It will make you think twice about visiting a strange church for Christmas.” It was also the first story of mine that CM Muller took for his wonderful journal, Nightscript. It was and still is a thrill to appear in the pages of that beautifully made book.

Very little-known fact––'The Sound That the World Makes' was going to be the title for my first collection––that is, until Michael Kelly of Undertow Press convinced me to change the title to Terrible Things. Good call, sir.

Last Ride of the Night

The decrepit amusement park in this story, “Cedar Grove Park”, is based on a real one that I won’t name here, since, (unbelievably) it’s actually still in operation. But all my home-town friends will know exactly what I’m talking about. The zoo was real too, although my memory of it is as foggy and nightmarish as the narrator’s––except for the smell. That smell was sharp as a knife.

I wrote the first long paragraph before I even knew there was going to be a story attached to it––I was just doing some free-style automatic writing about my memories of that place, and it ended up creating a world that was real and solid enough for those characters to step right into.

The little train that the characters ride is also real. Or used to be. One night when we were all in our twenties, a bunch of my friends and I did go out to that old amusement park on a whim, because we’d heard it was about to shut down. (It was always about to shut down, and probably still is.) The train had just stopped running for the night, but we convinced the guy to let us have one last ride. It really did take us way out into an open, chilly field. And in my memory, it did in fact stop somewhere in that dark field, though why it stopped, I can’t recall. I know this happened, because I have a photograph of us standing around the stalled train, grinning and laughing. I don’t remember how or when the train finally started again, but I know that it did, because I’m sitting here right now, typing this.

While the characters in the story are completely fictional, their feelings and situation, of course, are not. Everyone has felt trapped at one time or another, everyone carries their share of guilt, and everyone wants to be free from those painful states of mind, although we tend to choose the worst ways of doing that––until we choose something else.

'Last Ride of the Night' is one of two (maybe three) stories in the collection that end on a note of hope (or, as my old friend Mark said “at least conviction”). Not every horror story ends that way, but sometimes, once in a while, a little light gets in. And when it does, I’m always grateful.

This rather long story lay around unpublished for a while, as rather long stories tend to do. Then Ralph Robert Moore told me about a new anthology that Trevor Deyner was putting together for his Midnight Street Press, Ghost Highways. I sent it, and it was accepted. Many thanks to Trevor Deynor for giving this story a good home, and thanks, as always, to Ralph Robert Moore for the thoughtful heads-up.

The decrepit amusement park in this story, “Cedar Grove Park”, is based on a real one that I won’t name here, since, (unbelievably) it’s actually still in operation. But all my home-town friends will know exactly what I’m talking about. The zoo was real too, although my memory of it is as foggy and nightmarish as the narrator’s––except for the smell. That smell was sharp as a knife.

I wrote the first long paragraph before I even knew there was going to be a story attached to it––I was just doing some free-style automatic writing about my memories of that place, and it ended up creating a world that was real and solid enough for those characters to step right into.

The little train that the characters ride is also real. Or used to be. One night when we were all in our twenties, a bunch of my friends and I did go out to that old amusement park on a whim, because we’d heard it was about to shut down. (It was always about to shut down, and probably still is.) The train had just stopped running for the night, but we convinced the guy to let us have one last ride. It really did take us way out into an open, chilly field. And in my memory, it did in fact stop somewhere in that dark field, though why it stopped, I can’t recall. I know this happened, because I have a photograph of us standing around the stalled train, grinning and laughing. I don’t remember how or when the train finally started again, but I know that it did, because I’m sitting here right now, typing this.

While the characters in the story are completely fictional, their feelings and situation, of course, are not. Everyone has felt trapped at one time or another, everyone carries their share of guilt, and everyone wants to be free from those painful states of mind, although we tend to choose the worst ways of doing that––until we choose something else.

'Last Ride of the Night' is one of two (maybe three) stories in the collection that end on a note of hope (or, as my old friend Mark said “at least conviction”). Not every horror story ends that way, but sometimes, once in a while, a little light gets in. And when it does, I’m always grateful.

This rather long story lay around unpublished for a while, as rather long stories tend to do. Then Ralph Robert Moore told me about a new anthology that Trevor Deyner was putting together for his Midnight Street Press, Ghost Highways. I sent it, and it was accepted. Many thanks to Trevor Deynor for giving this story a good home, and thanks, as always, to Ralph Robert Moore for the thoughtful heads-up.